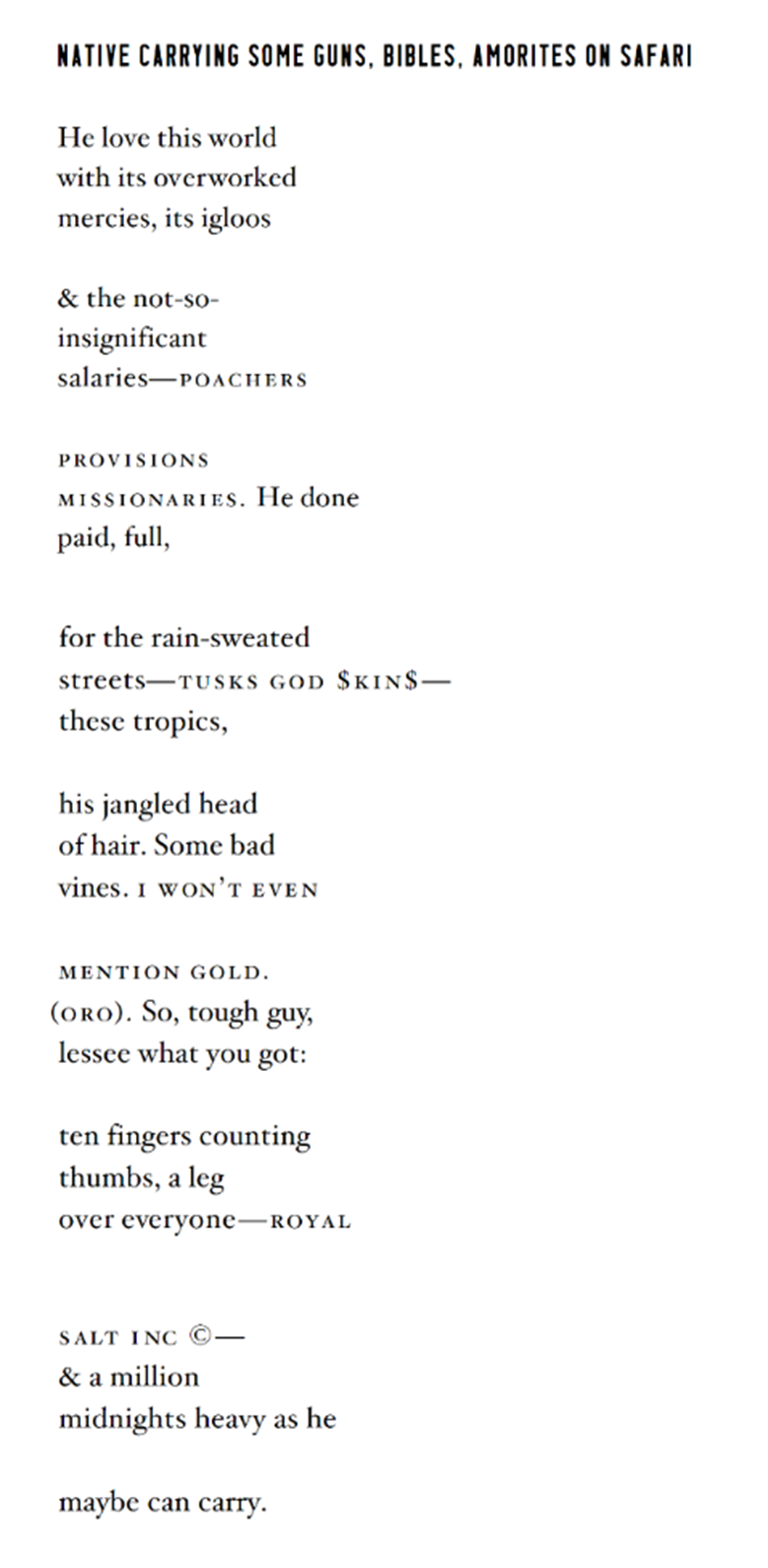

In Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari, 1982, a Black figure dominates the canvas, arms raised to the sky, confronting a colonial poacher. The present artwork evinces Basquiat's visual poetry, as layered linguistic meaning intertwines with vivid imagery to provoke thought and reflection on themes including slavery and empire. The exposed stretcher enhances its gritty narrative, infusing it with a raw, unrestrained essence and a near-sculptural presence characteristic of Basquiat’s celebrated stretcher paintings. Reduced to caricatures, Basquiat’s figures symbolise 'native' and 'coloniser.' They stand as a poignant critique of colonial commerce, encapsulating broader themes of colonisation, commercialisation, and African American history. In Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari, Basquiat's art amalgamates diverse cultural influences, ranging from the Bible to African tribal masks, with textual references to money, value, authenticity, and ownership. This synthesis creates a unique iconography reflective of his New York experience as well as his Caribbean ethnicity and West-African heritage.

Present work installed at The Brant Foundation, Jean-Michel Basquiat, March 6 – May 14, 2019. Image: Tom Powel Imaging, Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York The present work was created in 1982, a significant year in Basquiat's career marked by his first solo show in the United States, staged at Annina Nosei Gallery in New York. The work was first owned by the influential author Glenn O’Brien (and is in fact dedicated to him on the reverse), before being acquired by Francesco Pellizzi in 1983. An inspired collector and friend of the artist, Professor Pellizzi was the co-founder and editor of the journal Res, Anthropology, and Aesthetics, published by the Peabody at Harvard and Chicago University Press. Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari was first showcased in an exhibition dedicated to the Collection of Francesco Pellizzi, held at the Hofstra Museum in New York in 1989. It is prominently featured on the cover of the accompanying catalogue. The painting has been extensively discussed in the broader scholarly literature on the artist and has been featured in numerous highly acclaimed traveling retrospectives, including exhibitions organised by the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in 1992, the Brooklyn Museum in New York in 2005 and, most recently, the Brant Foundation in New York in 2019 where it was part of a dramatic salon-style wall grid of wooden support paintings from 1982.

"In Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari…it is the white explorer-trader-anthropologist (with his gun)—paired with the artist’s own grotesque black-self-caricature-as-the 'native'—that is nothing but a diaphanous outlined ghostly presence, framed by the evocation, in the surrounding ironic-sarcastic text of disjointed fragments of colonial 'history,' where narratives of invasion, exploitation, oppression, and slavery flicker about as remnants of half-learned, half-forgotten pedagogical chronicles."

— Francesco Pellizzi

Francesco Pellizzi seated in front of Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari, 1982, n.d. Photograph by Jeannette Montgomery Barron. Image: © Jeannette Montgomery Barron / Trunk Archive, Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari belongs to a distinctive group of paintings executed during Basquiat's meteoric ascent in 1982. This important work, distinguished by its exposed stretcher bars fixed at the corners, belongs to a series lauded by art critic Richard Marshall as Basquiat's 'most important group of paintings.'i Painted after severing ties with his former dealer and facing criticism from critics who argued that his rising international fame and ties to SoHo galleries were causing his work to lose its edge, the adoption of this daring new format signified that the young artist was unwilling to adhere to conventional norms.ii Basquiat introduced the first stretcher-bar paintings in an anarchic and intentionally 'messy' installation at his debut solo show at Patti Astor’s Fun Gallery on the Lower East Side in November 1982. The reception of the new work was overwhelmingly positive. Critic Nicolas Moufarrege proclaimed at the time that, 'the paintings [were] more authentic than ever.'iii Examples of the exposed stretcher bar paintings can be found in esteemed museum collections worldwide, including the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Broad Art Foundation in Los Angeles, the Menil Collection in Houston, and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

The present work illustrated on the cover of 1979–1989 American, Italian, Mexican Art from the Collection of Francesco Pellizzi, Hempstead, Hofstra Museum, Hofstra University; Bethlehem, Lehigh University Art Galleries, 1989 Marshall enthused that works with this unique construction embody Basquiat's deliberate dismantling of traditional canvas painting, infusing it with a raw, primitive aesthetic reminiscent of African shields and Spanish devotional objects.iv The visible stretcher on Basquiat’s canvas serves as the antithesis of a frame; it dismantles and de-frames the already unframed picture-object. Informal and overtly handmade, this structure imbues the history of painting on canvas—directly linked to the Western tradition of art—with a more sculptural, decorative, or functional legacy aligned with non-Western artistic practices. Additionally, it nods to a material vocabulary of assemblage and the found object, famously championed in postwar American art by neo-Dada practitioners like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

“Basquiat produced unprecedented combinations of words and images…that are actually sign-constructions, which, as representational wholes, acquire the disquieting nature of 'speaking objects' ... [The visible stretchers] also stress the work's character as a receptacle of signs… by Basquiat's implicit admission [this] would not have been possible without the precedent of Rauschenberg's vertiginously innovative and wholly American 'naïveté'”

— Francesco Pellizzi

Original Polaroid taken by Annina Nosei of the present work installed at her Prince Street gallery in the early 1980s. Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York The present work was completed in October 1982 at Basquiat’s new Crosby Street studio. Stephen Torton, his former studio assistant, was entrusted with sourcing materials to build the stretcher. 'I would go out in the middle of the night and find the stuff,' Torton recalls, likening the process to making sculpture.v Indeed, the simplicity of the support structure in the present work enhances the credibility and legitimacy of its raw expression. In conjunction with Basquiat’s opening at Fun Gallery a few weeks later, Rene Ricard highlighted the shift in the artist’s practice, writing a feature for the November issue of Artforum that exclaimed, 'He’s finally figured out a way to make a stretcher that…is so consistent with the imagery… They’re like something left in a small town after the carnival pulled out, hung in a shack, like a billboard in a migrant worker’s shed in a Walker Evans photo; they do look like signs, but signs for a product modern civilization has no use for.'vi

Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari brims with insouciant energy, characterised by drips, scrawls, outline used in suggestion of form, and textual interventions reminiscent of Basquiat’s past output as a street artist in the late 1970s. During this time, he gained prominence as a street poet using the pseudonym SAMO©, leaving his mark as a relentless tagger across the city's deteriorating infrastructure. Though the present work is executed on canvas rather than a public wall, Basquiat’s incorporation of visible wooden supports, extending beyond the picture plane and interacting with the surrounding space, powerfully evokes his deep-rooted connection to the urban environment, reminiscent of his formative years when the cityscape served as his primary canvas.

Andy Warhol, Little Electric Chair, painted in 1964-1965. Formerly in The Collection of S.I. Newhouse. Sold for $8,220,000 in Post-War and Contemporary Art Evening Sale on 15 May 2019 at Christie’s in New York. Artwork: © 2024 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Juxtaposing the rough-hewn materiality of the present work’s construction, its imagery is elegantly suspended within a clear and refined pictorial space. The syncopated rhythm of line, language, and insignia set against a spare, flat expanse of adobe or clay-like color conjures the flattened profile and hieratic logic of hieroglyphics or ancient cave paintings. Artist and critic Lorraine O’Grady recalls a conversation at Basquiat’s loft on Crosby Street sometime in the Spring of 1983 where he 'talked about art, performance, and the places he’d been.' O’Grady explains that, as they talked, 'he sat in the middle of a canvas writing with oilstick.'vii 'I’m not making paintings,' he said, 'I’m making tablets.'viii

“I’m always amazed at how people come up with things. Like Jean-Michel. How did he come up with the words he puts all over everything, his way of making a point without overstating the case, using one or two words he reveals a political acuity, gets the viewer going in the direction he wants, the illusion of the bombed-over wall.”

— Rene RicardWords in Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari wield as much power as his graphic iconography. By merging the 'cut-up' method popularised by poet William Burroughs with the sampling techniques pioneered by early hip-hop artists like Fab 5 Freddy, Basquiat fashioned artwork that was uniquely innovative yet deeply grounded in a rich linguistic legacy. In the present work, Basquiat leverages the inherent flexibility of language to forge a lyrical fusion of poetry and street-action art transposed onto canvas. Art historian Robert Storr termed the effect 'Eye Rap' in reference to the captivating visual rhythm and syncopation of Basquiat’s inimitable dialect.ix In Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari, Basquiat’s painted rap challenges linguistic representations of subjugation, oppression, and genocide. He scrawls 'MISSIONARIES,' 'POACHERS,' and 'CORTEZ,' inviting contemplation of the narrative associations evoked by these words.

The canvas is replete with billboard-style proclamations advertising '$KIN$' and 'TUSK$,' while the painting’s protagonist holds up his own sign-within-a-sign in the form of a crate with 'ROYAL SALT INC©' emblazoned on the front. This signboard, remarkably similar to the smaller works in Basquiat's stretcher-bar painting series, adds a captivating layer of comparison and self-referential imagery to the composition. Arrows and lines provide a semblance of order or enumeration, yet their rationale is solely visual; words are struck through, revised, hemmed in, punctuated, and underlined. At the bottom, beneath his crown, copyright claim, and codes of currency, Basquiat wryly opines 'I WON’T EVEN MENTION GOLD (ORO),' a fitting phrase for an artist who – even at the height of his success – delighted in questioning the value and nature of art.

"I cross out words so you will see them more; the fact that they are obscured makes you want to read them."

— Jean-Michel BasquiatBasquiat's aesthetic sensibilities were shaped by his upbringing in a richly diverse immigrant milieu, and his artistic concerns encompassed not only the enduring legacy of Africa in North America, but also extended to all forms of oppression and exploitation. In a comparably charged 1982 piece, The Whitney Museum of American Art’s Untitled (Plaid), Basquiat confronts the exploitation of Chinese labor in America by intertwining currency symbols with the stark declaration that the construction of the Western United States railroad was 'BUILT BY MEN OF CHINA FOR CHUMP CHANGE OF 1850.'

Robert Rauschenberg, K 24976 S, 1956.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania._569fa61c-071f-4464-8b44-f2d92c9a3b0b.jpg)

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Plaid), 1982.

The Whitney Museum of Art, New York. Image: Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala, Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

Robert Rauschenberg, K 24976 S, 1956.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania._569fa61c-071f-4464-8b44-f2d92c9a3b0b.jpg)

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Plaid), 1982.

The Whitney Museum of Art, New York. Image: Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala, Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

Through an integration of image and text in Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari, Basquiat directly addresses the conflicted history of Black and indigenous labor at the service of its own exploitation. Above the figures of a Black native and a white settler, the top text reads 'COLONIALIZATION: PART TWO IN A SERIES, VOL. VI,' connecting the image to an ongoing history of racial violence. Basquiat’s use of language was largely poetic and functioned as a commentary on the power of words to shape our understanding of the world. It becomes important to note specific connotations of meaning. While colonization is the process of establishing a colony, 'COLONIALIZATION' refers to 'the act of bringing into subjection or subjugation by colonializing,' implying the suppression of a people, in addition to the appropriation of pre-populated land.x

“In The Fire Next Time, James Baldwin declared that ‘for the horrors’ of black life ‘there has been almost no language.’ He insisted that it was the privacy of black experience that needed ‘to be recognized in language.’ Basquiat’s work gives that private anguish artistic expression.”

— Bell HooksIn Natives Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari, Basquiat undertakes a poignant exploration of the problematic concept of Primitivism within the context of colonialism. Through a masterful interplay of symbols and references, Basquiat deconstructs and confronts the notions of power, subjugation, and cultural erasure inherent in colonialist ideologies. The title itself, with its deliberate use of the term 'Natives,' immediately invokes the dehumanising lens through which colonial powers viewed indigenous peoples, relegating them to the status of the 'primitive' or the 'noble savage.' Basquiat astutely critiques this perspective by juxtaposing guns and Bibles, representing tools of physical and psychological control wielded under colonial rule. The presence of these objects underscores the dual mechanisms of coercion and cultural imperialism employed by colonisers. Compounding this, Basquiat incorporates a potent biblical allusion by referencing the Amorites, an ancient civilisation known for its classical culture and eventual conquest by the Hittites. By drawing parallels between this historical narrative and the contemporary realities of colonialism, Basquiat highlights the destructive impact of colonisation on indigenous cultures and traditions.

Charting a course from '

JOLLYGOOD MONEY IN SAVAGES' to 'GOD,' 'TUSK$,' and '$KIN$,' Basquiat’s use of dollar signs in place of s’s serves to ironise the exploitative ownership of both indigenous peoples and natural resources by colonial powers and Western capital. The deletion of the crown above the Black man's head, typically used by Basquiat to signify royalty, further serves as a potent commentary on the erasure of indigenous sovereignty and agency under colonial rule. He cites the names of historical colonisers, repeating variations of 'CORTEZ' like an incantation illustrating the interlocking presence of religion in the violent conquest of the Americas. An arrow points to 'GOLD, (ORO),' implicating Hernán Cortés, the Spanish conquistador responsible for the fall of the Aztec Empire in the 16th century. Above, 'LANDAU, BISHOP' has been crossed out, referencing Diego de Landa Calderón, a bishop of the Franciscan order and leader of the Spanish Inquisition in Yucatán who instituted a campaign against idolatry in the name of the church.

Left: Faustino Pérez, Solidarity with Zimbabwe, 1970. Published by OSPAAAL (The Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa & Latin America). The Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Right: Detail of the present lotCentral to the composition are two figures: a Black man holding a wooden sign bearing the logo 'ROYAL SALT INC©' and a heavily armed white man wearing a pith helmet of the kind routinely issued to European military personnel serving overseas in hot climates from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century. Here, Basquiat employs 'INC©' to imply the economic and political significance of controlling the distribution of natural products, linking it to human subjugation through his use of 'SALT' (followed by another, crossed-out copyright symbol) as a commodity reference. The symbol itself connotes a legally binding lifetime ownership, while the implication of its excessive use in this case evokes a nightmarish satire of greed. Primarily associated with the British Empire, the pith helmet, which Basquiat mocks in the present work with his reference to monarchy and use of the partially crossed-out Britishism '

JOLLYGOOD,' has come to be seen as an archetypal symbol of colonial power. In the 1970s, it even featured in poster art produced by OSPAAAL (The Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa & Latin America). Basquiat, born to Puerto Rican and Haitian parents, lived in Puerto Rico from 1974 to 1976, overlapping with the end of the island's Golden Age of Political Poster Art (1957–1973).xi This likely heightened his awareness of the highly politicized Puerto Rican art scene, particularly its focus on the colonial condition.In her 1993 essay for Artforum, where she deconstructs dismissals of Basquiat’s paintings by white critics who found them derivative or 'primitive,' Bell Hooks discussed Basquiat’s fragmented portrayal of the Black body as being 'half-formed or somehow mutilated.'xii Of the present work, she expounds that 'the black male body becomes, iconographically, a sign of lack and absence…The painting Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari (1982) graphically evokes images of incomplete blackness.'xiii The Black figure in the scene is simultaneously richly described and rigidly posed, an extension of the framing device holding a facsimile of itself, and still somehow fading away. The most detailed passage of multicolored acrylic and oilstick, the neck and head, still appears skeletal and see-through, with visible vertebrae and facial bones. More mask-like than human, it conjures a vocabulary of archetypal images rich with anthropological resonance.

He formed a strong and lasting bond with Robert Farris Thompson, a prominent scholar of African art, who, captivated by Basquiat's dynamic painting style, analyzed his work within the framework of post-colonial thought. Thompson acknowledged the potency of pieces like Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari, describing them as: 'Incantations of [Basquiat’s] blackness, incantations of what he was afraid of… He’s like a classical African drummer, just translating his nervousness into art. It was as if he was trying to turn his fears into creative energy.'xiv

“I’ve never been to Africa. I’m an artist who has been influenced by his New York environment. But I have a cultural memory: I don’t need to look for it, it exists. It’s over there, in Africa. That doesn’t mean that I have to go live there. Our cultural memory follows us everywhere, wherever we live.”

— Jean-Michel BasquiatIn Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari, Basquiat adopts a visual language used earlier by Picasso and the Cubists: facial features are simplified to a few shapes, including an exaggerated triangle nose and large rounded eyes, rendered deliberately in a 'primitive' style. In 1983, Diego Cortez, curator of New York/New Wave, bestowed upon Basquiat the title of the 'Black Picasso,' an association that was intended to be flattering but was ultimately demeaning. Nevertheless, the moniker was echoed by critics during his lifetime, who equated Basquiat’s rapid rise to widespread fame to Picasso’s celebrity, as well as mutual aesthetic interests. However, Basquiat’s engagement with European modernism is far from straightforward; it presents a complex, ambivalent relationship that defies easy classification. This complexity is exemplified in the present work, where Basquiat's intentionally 'primitive' rendering of facial features reflects his interest in non-Western masks as a means of cultural exploration from the perspective of a man of African descent. Concurrently, his engagement with the aesthetics of primitivism represents a self-aware critique of modernism's appropriation of such imagery. Thomas McEvilley fittingly described this as 'a canny reversal of tactics,' highlighting Basquiat's ironic subversion of European art history's influence. Basquiat here challenges established narratives, rewriting the dialogue to assert his own cultural perspective.

Through its poignant critique of the imposition of Western ideologies onto indigenous cultures, Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari, lays the groundwork for Basquiat's deeper engagement with grand historical themes. It foreshadows Basquiat's large-scale history paintings of 1983, which explore themes of the Black diaspora, power dynamics, and racial inequality, echoing concerns raised in the present work. As an important precursor to his iconic multi-panel narrative paintings, this painting exemplifies Basquiat's commitment to challenging dominant narratives and provoking critical reflection on history and society through his distinctive visual language.

Collector's Digest

Kevin Young is the Andrew W. Mellon Director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. He previously served as the director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. An award-winning author of fourteen books of poetry and prose, Young also serves as the poetry editor of the New Yorker. In 1991, just three years after Jean-Michel Basquiat’s death, Young began writing a series of poems inspired by the artist’s dynamic work. Individual verses from this series have appeared in The New Yorker, Grand Street, Gulf Coast, Hambone, and Global City Review. The following poem, inspired by the present work, is reproduced from the 2001 anthology To Repel Ghosts, Young’s ambitious homage to Basquiat’s life and legacy.

In 2021, a notable collaboration between Tiffany & Co. and the estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat brought the artwork Equals Pi into the public eye through an advertising campaign. Tiffany & Co. has also launched an Advents Calendar featuring the painting. Equals Pi, completed in the same prolific year as Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari, was previously unseen by the public and had been part of Tiffany's private collection. Equals Pi shares several thematic and stylistic elements with Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari. Both canvases are imbued with Basquiat's iconic visual language, which includes a complex interplay of text, vibrant colour, and symbolic imagery. In Equals Pi, Basquiat's use of cryptic symbols and equations challenges the viewer's perceptions of logic and mathematics, fields traditionally viewed as absolute and unerring. This interrogation of accepted norms mirrors the thematic challenge against historical narratives and colonial histories evident in Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari. This collaboration vividly demonstrates how Basquiat’s legacy remains highly influential, not only in terms of aesthetics and art history, but also how he is still an active participant in the ongoing conversations about the intersections of art, culture, luxury and commerce.

i Richard D. Marshall and Jean-Louis Prat, Jean-Michel Basquiat, vol. II, cat. Rais., Paris, 2000, p. 279.

ii M. Franklin Sirmans, ed., 'Chronology from exhibition Jean-Michel Basquiat at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York October 23, 1992-February 14, 1993,' The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat, updated 2018.

iii Nicolas Moufarrege, quoted in Pat Hoban, Jean-Michel Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art, London, 1998, p. 145.

iv Richard D. Marshall, 'Repelling Ghosts,' in Exh. Cat., Jean-Michel Basquiat, Palacio Episcopal de Malaga, Malaga, 1996, p. 140.

v Stephen Torton, quoted in Pat Hoban, Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art, London 1998, p. 172 and p.106

vi Rene Ricard, 'The Pledge of Allegiance,' Artforum, vol. 21, no. 3, November 1982.

vii Lorraine O’Grady, 'Basquiat and the Black Art World,' Artforum, vol. 31, no. 8, April 1993.

viii Jean-Michel Basquiat, quoted in Ibid.

ix Dieter Buchhart, ed., Words Are All We Have: Paintings by Jean-Michel Basquiat, exh. cat., New York, 2016.

x As defined in Collins English Dictionary

xi William Cordova, 'The Price of Chaufa: Sacred Cinema and the Roots of Revolutionary Celluloid,' The Brooklyn Rail, September 2022.

xii Bell Hooks, 'From the Archives: Altars of Sacrifice, Re-membering Basquiat,' Art in America, June 1, 1993.

xiii Ibid.

xiv Robert Farris Thompson, cited in Phoebe Hoban, Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art, New York 1998, p. 249.

Provenance

Glenn O’ Brien, New York (acquired directly from the artist)

Annina Nosei Gallery, New York (acquired from the above)

Francesco Pellizzi, New York (acquired from the above in 1983)

Thence by descent to the present ownerExhibited

Hempstead, Hofstra Museum, Hofstra University; Bethlehem, Lehigh University Art Galleries, 1979–1989 American, Italian, Mexican Art from the Collection of Francesco Pellizzi, 16 April–2 November, 1989, no. 3, p. 58 (illustrated on the front cover)

New York, Whitney Museum of American Art; Houston, The Menil Collection; Des Moines Art Center; Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Jean-Michel Basquiat, 23 October, 1992–9 January, 1994, pp. 138, 264 (illustrated, p. 138)

Houston, The Menil Collection, 17 Contemporaries: Artists from America, Italy, and Mexico - the Eighties, 11 June–15 August, 1999

Brooklyn Museum; Los Angeles, The Museum of Contemporary Art; Houston, The Museum of Fine Arts, Basquiat, 11 March, 2005–12 February, 2006, pp. 68, 224 (illustrated, p. 68)

Houston, The Menil Collection, NeoHooDoo: Art for a Forgotten Faith, 27 June–21 September, 2008, pl. 95, p. 14 (illustrated, n.p.)

Liverpool, Tate Museum, Afro-Modern: Journeys through the Black Atlantic, 29 January–25 April, 2010, pp. 18, 138-139, 214 (illustrated, p. 139)

New York, The Brant Foundation, Jean-Michel Basquiat, 6 March–14 May, 2019Literature

Helen A. Harrison, "Anthropologist Collects With a Passion", The New York Times, 30 April, 1989, p. 23

Bell Hooks, "Altars of Sacrifice, Re-membering Basquiat", Art in America, vol. 81, no. 6, June 1993, pp. 71-72 (illustrated, p. 72)

Richard D. Marshall and Jean-Louis Prat, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Paris, 1996, fig. 37, pp. 40–41, 48–49 (illustrated, p. 40)

Jean-Michel Basquiat, exh. cat., Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, Taipei, 1996, fig. 37, p. 116 (illustrated)

Tony Shafrazi, Jeffrey Deitch and Richard D. Marshall, Jean-Michel Basquiat, New York, 1999, pp. 164, 315 (illustrated, p. 164)

Richard D. Marshall and Jean-Louis Prat, Jean-Michel Basquiat, vol. II, Paris, 2000, fig. 35, no. 5, pp. 44–45, 140–141 (illustrated, pp. 45, 140)

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Evelyn Books Higginbotham, African American Lives, New York, 2004, p. 54 (illustrated)

Timothy Bewes, The Event of Postcolonial Shame, Princeton and Oxford, 2011, n.p. (illustrated on the front cover)

Doris Berger, Projected Art History: Biopics, Celebrity Culture, and the Popularizing of American Art, New York and London, 2014, p. 270, note 29

Jordana Moore Saggese, Reading Basquiat: Exploring Ambivalence in American Art, Berkley and Los Angeles, 2014, pl. 13, pp. 34-35, 122, 207 (illustrated, n.p.)

Ruth E. Iskin, ed., Re-envisioning the Contemporary Art Canon. Perspectives in a Global World, New York and London, 2017, p. 66

Jean-Michel Basquiat, exh. cat., Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, 2018, no. 5, pp. 302-303 (illustrated, p. 303)

Hans Werner Holzwarth, Benedikt Taschen and Eleanor Nairne, eds., Jean-Michel Basquiat and the Art of Storytelling, Cologne, 2018, pp. 170, 494 (illustrated, p. 170)Artist Biography

Jean-Michel Basquiat

American • 1960 - 1988

One of the most famous American artists of all time, Jean-Michel Basquiat first gained notoriety as a subversive graffiti-artist and street poet in the late 1970s. Operating under the pseudonym SAMO, he emblazoned the abandoned walls of the city with his unique blend of enigmatic symbols, icons and aphorisms. A voracious autodidact, by 1980, at 22-years of age, Basquiat began to direct his extraordinary talent towards painting and drawing. His powerful works brilliantly captured the zeitgeist of the 1980s New York underground scene and catapulted Basquiat on a dizzying meteoric ascent to international stardom that would only be put to a halt by his untimely death in 1988.

Basquiat's iconoclastic oeuvre revolves around the human figure. Exploiting the creative potential of free association and past experience, he created deeply personal, often autobiographical, images by drawing liberally from such disparate fields as urban street culture, music, poetry, Christian iconography, African-American and Aztec cultural histories and a broad range of art historical sources.

View More Works

BASQUIAT’S WORLD: WORKS FORMERLY FROM THE COLLECTION OF FRANCESCO PELLIZZI

Ο◆✱10

Native Carrying Some Guns, Bibles, Amorites on Safari

signed, titled, dedicated and dated '"NATIVE CARRYING GUNS + BIBLES AMORITES ON SAFARI" Jean-Michel Basquiat 1982 to Glenn O'Brien' on the reverse

acrylic and oil stick on canvas on wood supports

183.2 x 182.2 cm. (72 1/8 x 71 3/4 in.)

Executed in 1982.

Estimate

HK$90,000,000 - 120,000,000

€10,620,000-14,160,000

$11,540,000-15,380,000

Sold for HK$98,735,000

Danielle So

Specialist, Head of Evening Sale

+852 2318 2027

danielleso@phillips.com

Modern & Contemporary Art Evening Sale

Hong Kong Auction 31 May 2024

7

This lot is no longer available.

15

This lot is no longer available.