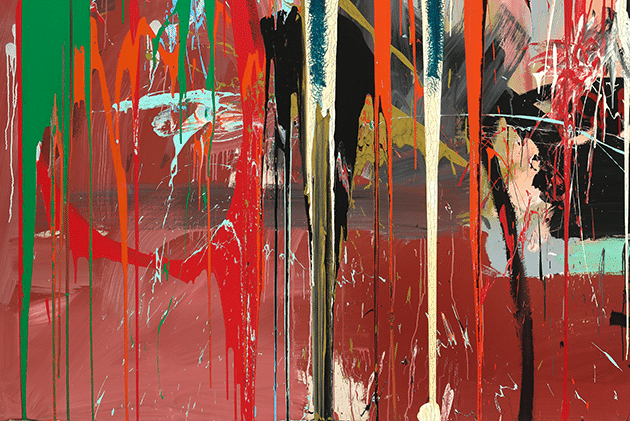

Coming from the esteemed collection of Japanese entrepreneur Yusaku Maezawa, Untitled is one of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s greatest masterpieces. Its potency and scale mark it as one of his most ambitious works: standing at almost eight feet tall and over 16 feet wide, it is among his largest canvases. Executed in 1982, the watershed year which shot the artist to international stardom, this tour de force is from a small series created in Modena, Italy, where Basquiat visited at the invitation of the dealer Emilio Mazzoli during two periods in the early 1980s.

This pivotal chapter, today regarded as one of the most desirable of his career, marked his transition from “SAMO©”—the pseudonym Basquiat used as a street poet and tagger whose nom de plume had begun appearing all over New York’s disintegrating infrastructure in the 1970s—to an art world force to be reckoned with. Indeed, Untitled’s vastness is so striking that it, coupled with the artist’s use of spray paint and geometric shapes, is suggestive of a large mural or graffiti-covered city wall—a fusion of street culture with “high art” that reflects a radical shift in his career and approach to art-making.

"I don’t think about art while I work. I try to think about life."

—Jean-Michel BasquiatThis extraordinary work was made just months after René Ricard’s watershed essay on Basquiat, “The Radiant Child,” introduced the painter to the upper echelons of art society by situating him within the modern canon. “He has a perfect idea of what he is getting across, using everything that collates his vision,” Ricard expressed. “If Cy Twombly and Jean Dubuffet had a baby and gave it up for adoption it would be Jean-Michel. The elegance of Twombly is there [and is] from the same source (graffiti) and so is the brut of the young Dubuffet.”i

Characterized by an unparalleled painterly dynamism, Untitled embodies both the gestural lyricism and rawness that Ricard described. The work depicts a devil figure with blood red paint dripping from his horns. This demonic subject, whose body is defined only by black strokes delineating ribs, rises against a fiery expanse of gestural color evoking the physicality of Abstract Expressionism. Appearing with arms or wings spread across the canvas, he meets the viewer with a threatening grin and stares at us with piercing eyes. These exaggerated features—including an oversized triangular nose and a grid of teeth—immediately resonate as both a nod to the African masks that he admired and as a reply to European modernism’s “primitive” aesthetic.

The central figure’s primary identifiable characteristic beyond his devilish identity is a head of short, gravity-defying dreadlocks; considering their resemblance to the artist’s distinctive hairstyle which he began to wear after cutting off his blonde mohawk around this time, Untitled is certainly at least partially a self-portrait. However refracted, it is a manifestation of a pivotal moment when his image of himself—and the art world’s image of him—was rapidly evolving. Untitled is unequivocally one of the finest examples of the distinctive iconography and painterly prowess that triumphantly marked the peak of his all-too-short career.

1982: The Birth of Jean-Michel Basquiat

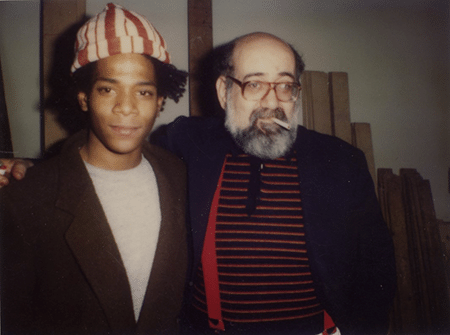

Annina Nosei and Jean-Michel Basquiat in his studio in the basement of the Annina Nosei Gallery, New York, 1982. Image: © Naoki Okamoto, Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York Basquiat first came to prominence in early 1981, a year before the execution of Untitled, when he was included in New York/New Wave, a groundbreaking multi-disciplinary exhibition surveying the city’s burgeoning avant-garde scene at P.S.1, Institute for Art and Urban Resources, Inc., in Long Island City. Still billed under “SAMO©,” he was the only artist to be given a prominent space in the show to exhibit paintings.

The show propelled him to overnight success. Not only did his raw, expressive dynamism win the admiration of nearly every critic, but he also caught the attention of gallerists Emilio Mazzoli, Annina Nosei, and Bruno Bischofberger—an international cohort of dealers with strong collector relationships who would become virtually responsible for catapulting his career. Mazzoli soon invited Basquiat to Modena, offering the young artist—still known as “SAMO©”—the first one-man show of his career in the spring of 1981 at his gallery. In addition to introducing him to the European art world, the sold-out exhibition endowed Basquiat with a fresh confidence in his transition from street culture to the commercial art world.

Basquiat with Emilio Mazzoli, 1981 Upon his return to New York, Nosei provided him with many of the tools he was lacking: canvases, high-quality paints, and a dedicated studio space in her gallery basement. In March 1982, she gave him his debut solo show as Jean-Michel Basquiat, which at last shed his former “SAMO©” identity and solidified his reputation as a major force in the Neo-Expressionist art scene. Around this time, at only 21 years old, he became the youngest artist to be invited to participate in the landmark Documenta VII exhibition in Kassel, Germany, scheduled for the summer of 1982. Energized by this as well as a string of other career-launching exhibitions, Basquiat spent the pivotal year executing depictions of himself and those close to him with invigorated passion—pictures which today are widely considered to be the finest of his career. “For Basquiat, it all converges in 1982,” Jeffrey Deitch, the prominent art dealer and the artist’s close friend, conveyed. “Those of us who were there at the time and saw those paintings just couldn’t believe it. The level of achievement was just astonishing. It was almost a miracle.”ii

"[In 1982] I made the best paintings ever."

—Jean-Michel BasquiatBasquiat returned to Modena in spring of 1982, where he began work on a series of approximately eight career-defining paintings in preparation for a second planned exhibition at Galleria d'Arte Emilio Mazzoli. Set up by the gallerist in a massive industrial working space, he was able to work on a much larger scale than Nosei’s basement studio allowed. It was during this time that he executed three of the groundbreaking pictures, almost certainly self-portraits, that have made this chapter one of the most sought after of his oeuvre: Untitled, Profit 1, and Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump. Later feeling pressured to work at an unreasonable pace in order to satisfy the dealer’s expectations and complete the remainder of the show, Basquiat canceled the exhibition, returning to the U.S. and soon after severing ties with both Mazzoli and Nosei.

Characterized by their monumentality, bold palette, and large foregrounded figures, these three masterpieces emanated self-assurance from his newfound international success. “His peers had already anointed him as the best artist in the community, and he had the accolades of ‘New York/New Wave,’” which inspired “an increased confidence in the painting: in the strength, in the line,” according to Deitch.iii They reflect an artist not only working at his prime, but one coming into his own: unwilling to acquiesce to dealer demands, Basquiat executed these works when he was finally becoming assertive enough to work at his own pace and on his own terms.

"Everybody around him knew that these [1982 paintings] were extraordinary."

—Jeffrey Deitch

The Modena Masterpieces

The Guilt of Gold Teeth, 1982. Private Collection. Image: Erik Pendzich / Alamy Stock Photo, Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

Profit I, 1982. Private Collection. Image: © Christie's Images / Bridgeman Images, Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump, 1982. Collection of Ken Griffin, on loan to the Art Institute of Chicago. Image: akg-images, Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

Untitled (Angel), 1982. Private Collection. Image: Adagp Images, Paris, / SCALA, Florence, Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

The Guilt of Gold Teeth, 1982. Private Collection. Image: Erik Pendzich / Alamy Stock Photo, Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

Profit I, 1982. Private Collection. Image: © Christie's Images / Bridgeman Images, Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

School of MoMA

When Basquiat was as young as five years old, his mother began taking him to cultural venues across his native New York City, including the Brooklyn Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Modern Art. These formative memories provided him with a robust art historical repertoire, an extensive internal library of images which his work would reference time and time again. Though he much admired the Old Masters, visits to the MoMA were perhaps his favorite. “Jean knew every inch of that museum,” the artist’s girlfriend Suzanne Mallouk later recalled, “every painting, every room.”iv

Jackson Pollock, Blue Poles, 1952. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Image: © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra / Purchased 1973 / Bridgeman Images, Artwork: © 2022 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York "[Basquiat] was very knowledgeable about it all…from abstract practitioners like Pollock, de Kooning and Rothko, to old masters like Caravaggio."

—Fab 5 Freddy (Fred Brathwaite)It was at MoMA where Basquiat first encountered the work of several of the most significant figures of the 20th century art historical canon. He recalled feeling awestruck there by Claude Monet’s colossal Water Lilies, the scale and impasto-rich surfaces of which find an affinity with the present work. It was there that he also was likely introduced to the work of Franz Kline, which Basquiat himself acknowledged as among his greatest influences; the black ribs of Untitled’s central figure and the multicolored vertical gestures that surround him are reminiscent of the Abstract Expressionist’s signature linear strokes. Basquiat no doubt also saw Jackson Pollock’s revelatory “drip” paintings there, which are evoked by the liquescent flurry of bursts, splashes, and daubs across the expanse of the present work.

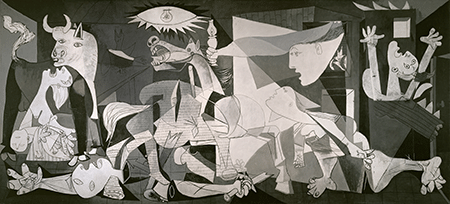

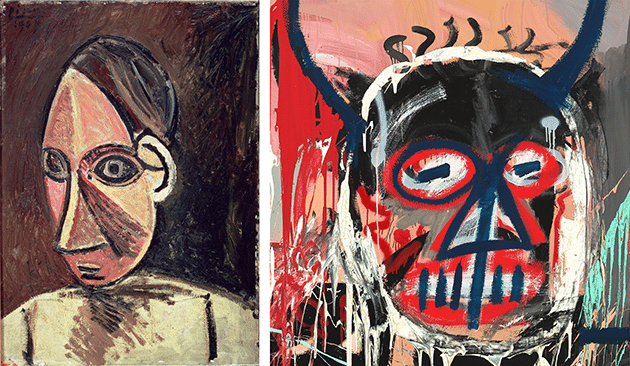

Of all these hallmarks of modernism that Basquiat first viewed as a child at MoMA, however, it was Pablo Picasso who made the most significant impact. In a 1985 interview, Basquiat recalled: “Probably seeing Guernica was my favorite thing as a kid.”v On a high school trip as a teenager, he became reacquainted with the work, which remained on extended loan at MoMA until it was returned to Spain in 1981.

Basquiat’s encounters with Picasso’s Guernica have been much mythologized—by both the artist, who emphasized its impact on him, and his most devout fans. Indeed, in the opening credits of Julian Schnabel’s 1996 biopic, the young painter and his mother stand before the iconic image; as she weeps, overcome by emotion, Basquiat stares up at the picture while a golden halo appears on his head in a magical anointment foreshadowing his artistic destiny. These visits to MoMA during his formative years birthed a career-long, impassioned engagement with both Picasso’s oeuvre and art history—one that was simultaneously critical and awestruck, irreverent and devoted.

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1914-1926. Museum of Modern Art, New York. Image: © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY Angels and Demons

Executed in 1937, Guernica was Picasso’s loudest political statement. The grisaille painting, which stands over 11 feet wide, was a manifestation of the artist’s outrage towards the German bombing of the Basque city after which the work is named. A plea against the terror and barbarity of the Spanish Civil War and a warning of what World War II would bring, this work is renowned as one of the most evocative and powerful images of the 20th century. A gored horse, a terrified woman with her arms raised, a weeping Madonna holding her dead baby, and other suffering figures compose a scene of intense anguish before a wide-eyed bull. Interpreted by many to symbolize Francisco Franco or the Fascist state, the sinister bull, seemingly devoid of apathy, was said by Picasso to signify “brutality and darkness.”vi

The monumental, horizontal format of Untitled has caused it to be likened to Guernica, and though Basquiat was no doubt struck by the compositional form so reminiscent of graffiti-covered walls, he also would have been intrigued by the iconography of the bull. Another one of Basquiat’s recurrent motifs, the bull bears a strong visual resemblance to his devil—they share horns, bold eyes, and an aggressive snarl with visible teeth.

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937. Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid. Image: Art Resource, NY, Artwork: © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York The bull was an enigmatic symbol during this period in Picasso’s career: images from his series of prints titled The Dream and Lie of Franco, also executed in 1937, depict a heroic bull fighting and goring Franco, an overt representation of the will of the Spanish people to overthrow their dictator. In this sense, Picasso used the animal as a visual device to rupture the dichotomy of good and evil, a thematic thread weaving together his entire oeuvre.

"Seeing Guernica was my favorite thing as a kid."

—Jean-Michel BasquiatIt is no surprise that of all Guernica’s figures, Basquiat’s self-portrait would most closely resemble the chilling bull overseeing the horrific scene. Like Picasso, Basquiat was fascinated by the binary opposition of “good/evil,” and was especially driven to explore what identities embodied these representations historically. In this way, Untitled marks a distinct contrast to the artist’s depictions of Black martyrdom and embodies his interest in the dualities of heaven and hell, good and evil, and sacred and sinful. The very strong compositional and formal affinity that the present work shares with another painting Basquiat executed in 1982 in Modena, Untitled (Angel), implies that the two central figures could easily be reversed; the holy collapses into the blasphemous.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Pink Devil, 1982. The Broad, Los Angeles. Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York These Modena self-portraits are replete with such juxtapositions that blur the lines between goodness and evil: while in Profit I, Basquiat rendered himself as a sacred figure crowned with a nimbus, arms raised against a jet black expanse, in Untitled he is a devil ironically surrounded by an ebullient rush of color. These unexpected contexts, heaven and hell exchanged, underscore the duality that Basquiat considered to be central to humanity. Evoking Picasso in its disruption of set notions of good and evil, the present work serves as a reminder that these distinctions are porous, interrelated, and inherently defined by each other.

The “Primitive” Devil Incarnate

Basquiat’s engagement with Picasso and European modernism was much richer than just his formative encounters with Guernica. It was a complex, ambivalent relationship that is impossible to classify—one that was rife with homages to and subversions of Western art history.

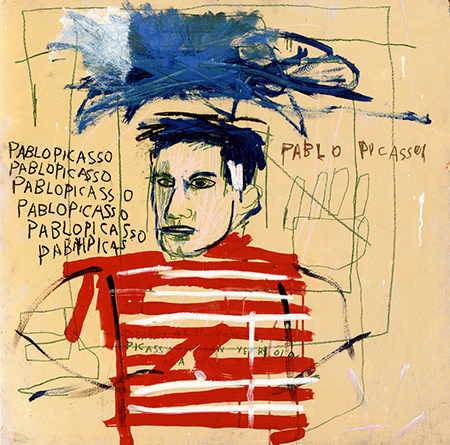

It was first and foremost Picasso’s influence that permeated Basquiat’s work in immeasurable ways. In an interview, he revealed that he acquired a 1922 painting by Picasso that “took all [his] money”; he also dedicated at least a few paintings to the Spanish master.vii In Untitled (Pablo Picasso), 1984, what appears to be a portrait of the painter in his signature sailor jersey has also been read as a self-portrait of Basquiat, with the broad nose and unkempt dark hair that he typically used to depict himself blurring the two’s identities. Crediting the vitality of works such as Untitled to Picasso’s impact, curator and art historian Richard Marshall emphasized that “Picasso’s work gave Basquiat the authority and the precedent to pursue his own brash and aggressive self-portraits.”viii

Untitled (Pablo Picasso), 1984. Private Collection. Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York The kinship Basquiat held with his modernist forebear was palpable to many others as well. In 1983, just one year after the present work was executed, Diego Cortez, the curator behind New York/New Wave, published a short text deeming him the “Black Picasso,” a designation which was echoed by critics throughout Basquiat’s lifetime. An association that was intended to be flattering but was ultimately demeaning, this label proliferated because of Basquiat’s rapid rise to widespread fame, which was equated to Picasso’s celebrity, as well as mutual aesthetic interests.

"Both activist and parodist, [Basquiat] uses the marks and gestures of white Modernist masters to redraw their own civilization as an archaeological ruin of the dream of its own future."

—Thomas McEvilleyA primary visual theme that united them was “primitivism,” a mode of representation that idolized “primitive” cultures and appropriated motifs found in the art of non-Western peoples; primitivism was especially present in European modernist art and often perpetuated racist beliefs regarding non-white nations. In many ways, this imagery deeply informed the lexicon of Cubism, whose proponents were engrossed with the stylized and dramatic geometric reduction of form found in African and Oceanic sculptures and masks.

Untitled draws on the same aesthetic language as Picasso and the Cubists: the facial features are represented by only a few shapes, including an exaggerated triangle nose and large rounded eyes, which are rendered in a deliberately “primitive” manner. On one hand, this common lineage is reflective of Basquiat’s fascination with non-Western masks, which became a means of cultural exploration throughout his career from the perspective of a man of African descent born to Puerto Rican and Haitian parents.

[left] Pablo Picasso, Head of a Woman (Tête de femme), 1907. Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia. Image: © Barnes Foundation / Bridgeman Images, Artwork: © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York [right] Detail of the present work On the other, Basquiat’s invocation of primitivism was always also rooted in a self-aware, ironic inversion of modernism’s relationship with it, and was what Thomas McEvilley called “a canny reversal of tactics from the white art tradition, a reversal that resonates with assertions, ironies, and claims.” In this sense, Untitled takes aim at modernism and its co-option of “primitive” iconography; European art history was his greatest influence but also his biggest target. By rendering himself as a devil using this imagery, Basquiat ridiculed the art establishment’s historic debasement of non-Western cultures. Though Cubism had not been a dominant force in the European avant-garde for over a half-century before the execution of Untitled, his derision of art world prejudice still rang true: in 1982, Hal Foster named Basquiat the “new art-world primitive,” and a review of Documenta VII later that year called him “a true primitive.”x,xi The present work’s self-caricaturization can thus be read as a response to being routinely reduced to his Blackness, whether that be explicitly as a “primitive” or in a veiled compliment as the “Black Picasso.”

"I'm not a Black artist, I'm an artist."

—Jean-Michel Basquiat“As a person of African descent, frequently plagued by myths of primitivism,” Jordana Moore Saggese asserted, “Basquiat was surely invested in the irony of a modern art history that systematically excludes artists of African descent while remaining indebted to them.” A self-portrait through the eyes of the predominately white art world Basquiat circumnavigated, Untitled reflects the struggles the artist faced even while being regarded as one of the leading figures of post-war American art.

Legacy of a Masterpiece

Untitled installed at Galerie Enrico Navarra, Paris, 1996. Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York One of Basquiat’s greatest works, Untitled epitomizes the fresh vigor and idiosyncratic visual language that marked an unparalleled moment in his career. Since its execution, it has been renowned as one of the most iconic examples of Basquiat’s radical approach, even gracing the cover of the artist’s 1996 catalogue raisonné.

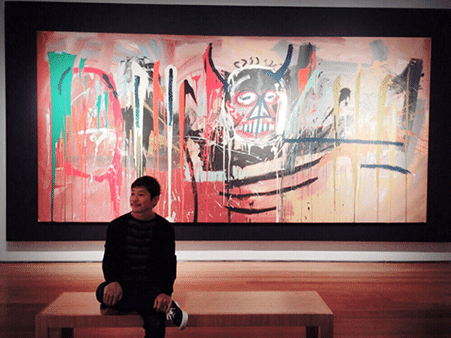

Despite its monumental size, the work has traveled around the world as a centerpiece in several of the artist’s major retrospectives. From Taiwan to France and Brazil to Italy and Germany, this masterpiece has awed Basquiat devotees across the globe and has stood as a symbol of his extraordinary oeuvre for art historians and the public alike. Its singularity was again solidified when it set the world auction record for the artist in 2016, igniting a renewed market appreciation for the artist’s work.

Returning for the first time to Japan since it was first exhibited at Akira Ikeda Gallery in Tokyo in 1985, the work has been a focal point of Maezawa’s collection for the last six years. “When standing in front of Untitled, it is overwhelmingly powerful yet melancholic, and this makes me feel a sense of euphoria and despair at the same time,” Maezawa reflected. “I believe that art collections are something that should always continue to grow and evolve…Living with this art piece has made my love and interest for art deeper and stronger. I cannot begin to explain the influence that this masterpiece has had in my life, and I am certain it will be an unforgettable work for me.”

Yusaku Maezawa with Untitled. Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

i René Ricard, “The Radiant Child,” Artforum, vol. XX, no. 4, December 1981, p. 43.

ii Alexxa Gotthardt, “What Makes 1982 Basquiat’s Most Valuable Year,” Artsy, April 1, 2018, online.

iii Ibid.

iv Suzanne Mallouk, quoted in Olivia Laing, “Race, power, money—the art of Jean-Michel Basquiat,” The Guardian, September 8, 2017, online.

v Jean-Michel Basquiat, quoted in “Interview by Becky Johnston and Tamra Davis,” The Jean-Michel Basquiat Reader: Writings, Interviews, and Critical Responses, Berkeley, 2021, p. 52.

vi Pablo Picasso, quoted in an interview with Jerome Seckler [1945], Dore Ashton, Picasso on Art: A Selection of Views, London, 1972, pp. 137, 139.

vii Jean-Michel Basquiat, quoted in “Interview by Becky Johnston and Tamra Davis,” The Jean-Michel Basquiat Reader: Writings, Interviews, and Critical Responses, Berkeley, 2021, p. 60.

viii Richard Marshall, “Repelling Ghosts,” in Richard Marshall, Jean-Michel Basquiat, exh. cat., Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1992, p. 16.

ix Thomas McEvilley, “Royal Slumming: Jean-Michel Basquiat Here Below,” Artforum, November 1992, p. 96.

x Hal Foster, “Between Modernism and the Media,” Art in America, summer 1982, p. 15.

xi Noel Frackman and Ruth Kaufmann, “Documenta 7: The Dialogue and a Few Asides,” Arts Magazine, October 1982, 97.

xii Jordana Moore Saggese, The Jean-Michel Basquiat Reader: Writings, Interviews, and Critical Responses, Berkeley, 2021, p. 4.Video

Lot 12 | Jean-Michel Basquiat

Provenance

Annina Nosei Gallery, New York

Akira Ikeda Gallery, Nagoya (acquired from the above in 1985)

Tsurukame Corporation, Japan

Akira Ikeda Gallery, Nagoya

Enrico Navarra Gallery, New York (acquired from the above)

Hanart TZ Gallery, Hong Kong (acquired from the above)

Private Collection, New York (acquired from the above)

Sotheby's, London, June 23, 2004, lot 32

Amalia Dayan and Adam Lindemann, New York (acquired at the above sale)

Christie’s, New York, May 10, 2016, lot 36B

Acquired at the above sale by the present ownerExhibited

Tokyo, Akira Ikeda Gallery, Jean-Michel Basquiat: Paintings, December 2–25, 1985, no. 4, n.p. (illustrated)

Chiba, Makuhari Messe, Pharmakon '90, July 28–August 20, 1990, p. 438 (illustrated, pp. 74-75)

Paris, Galerie Enrico Navarra, Jean-Michel Basquiat. Peintures, April 2–June 12, 1996

Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts; Taichung, Taiwan Museum of Art, Jean-Michel Basquiat, January 26–June 15, 1997, pp. 36-37 (illustrated)

Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, Jean-Michel Basquiat, June 16–August 23, 1998, pp. 50, 116 (illustrated, pp. 51-53; Galerie Enrico Navarra, Paris, 1996, installation view illustrated, p. 111)

Venice, Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa, Basquiat a Venezia, June 9–October 3, 1999, p. 149 (illustrated, pp. 62-63, 114; Galerie Enrico Navarra, Paris, 1996, installation view illustrated, p. 134)

Naples, Il Museo Civico di Castel Nuovo, Basquiat a Napoli, December 19, 1999–March 4, 2000, pp. 60-61 (illustrated)

Rome, Chiostro del Bramante, Jean-Michel Basquiat: Dipinti, January 20–March 17, 2002, pp. 70-71 (illustrated)

Paris, Fondation Dina Vierny-Musée Maillol, Jean-Michel Basquiat. The Work of a Lifetime, June 27–October 23, 2003, pp. 44-45 (illustrated; Galerie Enrico Navarra, Paris, 1996, installation view illustrated, p. 161)

Basel, Fondation Beyeler (no. 47, pp. 66-67, illustrated); Musée d'Art moderne de la Ville de Paris (no. 45, pp. 70-71, illustrated), Basquiat, May 9, 2010–January 30, 2011Literature

Nobuyuki Hiromoto, "Rhythmical and Perfect Balance," Monthly Art Magazine Bijutsu Techo, vol. 38, no. 564, July 1986, pp. 81-80 (illustrated)

Jean-Louis Prat and Richard Marshall, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Paris, 1996, vol. 1, p. 389 (illustrated, pp. 76-77 and on the front and back covers); vol. 2, p. 249 (Galerie Enrico Navarra, Paris, 1996, installation view illustrated)

Tony Shafrazi, Jeffrey Deitch and Richard Marshall, Jean-Michel Basquiat, New York, 1999, pp. 110-111 (illustrated)

Galerie Enrico Navarra, ed., Jean-Michel Basquiat, Paris, 2000, vol. 1, pp. 72-73 (illustrated); vol. 2, no. 2, p. 99 (illustrated, p. 98); vol. 3, pp. 72-23 (illustrated); appendix, p. 46 (Fondation Beyeler, Basel, 2010, installation view illustrated)

Adam Lindemann, Collecting Contemporary Art, Cologne, 2010, p. 129 (illustrated)

Koji Ozawa, "Yusaku Maezawa, who lives and shares his art," GQ Japan, August 16, 2016, online (installation view illustrated)

Hans Werner Holzwarth, ed., Jean-Michel Basquiat and the Art of Storytelling, Cologne, 2018, p. 494 (illustrated, pp. 200-201)Artist Biography

Jean-Michel Basquiat

American • 1960 - 1988

One of the most famous American artists of all time, Jean-Michel Basquiat first gained notoriety as a subversive graffiti-artist and street poet in the late 1970s. Operating under the pseudonym SAMO, he emblazoned the abandoned walls of the city with his unique blend of enigmatic symbols, icons and aphorisms. A voracious autodidact, by 1980, at 22-years of age, Basquiat began to direct his extraordinary talent towards painting and drawing. His powerful works brilliantly captured the zeitgeist of the 1980s New York underground scene and catapulted Basquiat on a dizzying meteoric ascent to international stardom that would only be put to a halt by his untimely death in 1988.

Basquiat's iconoclastic oeuvre revolves around the human figure. Exploiting the creative potential of free association and past experience, he created deeply personal, often autobiographical, images by drawing liberally from such disparate fields as urban street culture, music, poetry, Christian iconography, African-American and Aztec cultural histories and a broad range of art historical sources.

View More Works

Property from the Collection of Yusaku Maezawa

Ο◆12

Untitled

signed, inscribed and dated "JEAN MICHEL BASQUIAT MODENA 1982." on the reverse

acrylic and spray paint on canvas

94 1/4 x 197 1/4 in. (239.4 x 501 cm)

Executed in 1982.

Please note this Lot is a Premium Lot. To bid on the Lot, you must complete and satisfy our Premium Lot pre-registration procedure no later than 24 hours before the start of the Auction. Please also note that all bidders must place bids in person, via absentee bid, or by telephone. Contact the Department for further details.

Estimate On Request

Sold for $85,000,000

Amanda Lo Iacono

Global Managing Director and Specialist, Head of Evening Sale, New York

+1 212 940 1278

ALoiacono@phillips.com

Carolyn Mayer

Associate Specialist, Associate Head of Evening Sale, New York

+1 212 940 1206

CMayer@phillips.com

20th Century & Contemporary Art Evening Sale

New York Auction 18 May 2022

31

This lot is no longer available.