2Ο◆

Matthew Wong

Untitled

- Estimate

- $1,000,000 - 1,500,000

Further Details

“What would it look like, If you tried to paint in solitude?”Matthew Wong's Untitled, 2017 exemplifies his unique approach to landscape painting, showcasing the artist’s evolving exploration of nature as a space for emotional reflection and solitude. The present work was created during a key year in Wong's meteoric career, when he gained institutional recognition through the Dallas Museum of Art’s acquisition of a contemporaneous painting titled The West, 2017. Drawing on Modernist traditions and the emotive qualities of Abstract Expressionism, Untitled reveals Wong’s intuitive approach to painting, resulting in a landscape that is both dreamlike and deeply personal.—Matthew Wong

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Nocturne: Blue and Silver - Chelsea, 1871. Tate, London. Image: Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Lone wanderers frequently appear in Wong’s work, threading their way through serpentine paths and kaleidoscopic rivers in surreal dreamscapes, always journeying but never quite arriving at a final destination. In Untitled, the mysterious journey unfolds along a multicolored waterway flowing inward and upward from lower right. A shadowy figure steers a small boat along the river’s winding path, navigating between dense walls of wild green vegetation on either side. On the left, a dog watches, perhaps partially hidden by the branches of an overhanging tree, its presence unnoticed by the passing boater, who in turn faces away from the viewer. Wong often referred to such figures as “pilgrims,” Lilliputian travelers crossing vast, overwhelming landscapes. As critic John Yau observes, these apparitions “disturb the landscape” and “can be read as surrogates for the artist working his way through the landscape of art; he is both embedded in the paint and having a dialogue with it.”i In Untitled, Wong depicts a figure “literally surrounded by paint,” immersed in a whirlwind of rhythmically contrasting brushstrokes and colors that highlight its limited perspective, unable to see beyond the tilted horizon.ii

“Wong makes myriad lines, dots, daubs, and short, lush brushstrokes, eventually arriving at an imaginary landscape.... A painterly cartographer, Wong literally feels his way across the landscape, dot by dot, paint stroke by paint stroke.”—John Yau, Hyperallergic, 2018

Wong’s portrayal of isolation transcends the lone figure, using the landscape as an emotional and psychological mirror. The swirling brushstrokes and textured layering of colors suggest a world both vibrant and suffocating, reflecting the internal overwhelm of loneliness. Wong’s topography blurs the line between the external environment and the inner psyche, where vast, teeming natural spaces symbolize emotional isolation. The verdant greens and turquoise hues of the foliage are punctuated by dappled bursts of color that suggest light filtering through the trees. The figure, dressed in red, stands in stark contrast to the landscape, heightening the sense of disconnection and reinforcing their solitude. As Wong observed, “Living a fairly reclusive life and finding the most stimulation and enjoyment from matters of the mind... it’s inevitable that the solitary nature of this pattern seeps into and informs my work.”iii In Untitled, the contrast between the figure and their surroundings amplifies the melancholic tone, as the individual, lost in a world that is beautiful yet indifferent, becomes a visual metaphor for the isolation and introspection that permeates much of Wong’s art, a poignant reflection of the quiet loneliness in his life and work.

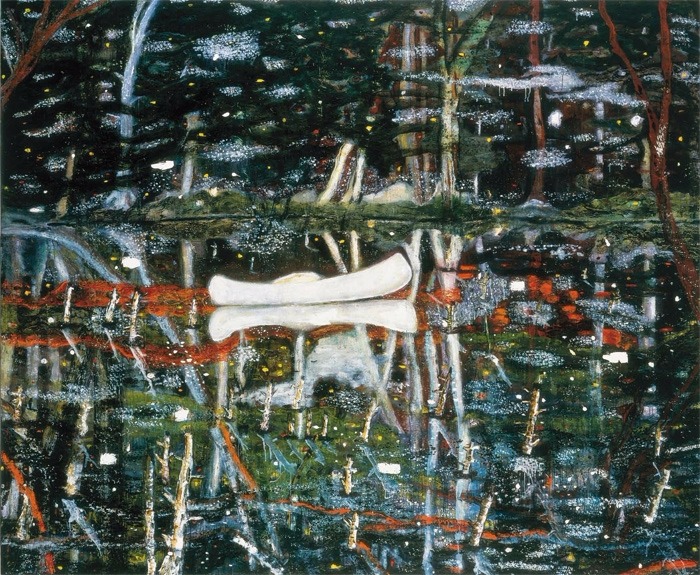

Peter Doig, White Canoe, 1990/1991. Private Collection. Formerly Saatchi Collection, London. Artwork: © 2024 Peter Doig/Artsts Rights Society (ARS), New York

“I would like my paintings to have something in them people across the spectrum can find things they identify with. I do believe that there is an inherent loneliness or melancholy to much of contemporary life, and on a broader level I feel my work speaks to this quality in addition to being a reflection of my thoughts, fascinations and impulses.”—Matthew Wong

In Untitled, Wong’s inclusion of a boat, much like the canoes in Peter Doig’s paintings—often empty or sparsely inhabited and floating in dreamlike, moonlit settings that evoke absence or reflection—serves as a vessel for drifting between states of memory and consciousness. Similarly, the figure in this painting, outlined in a glowing white aura, appears suspended in a transcendent space, reinforcing a sense of detachment from the world. The weeping tree on the left, with its long, drooping branches, enhances the mood of quiet contemplation, while vibrant splashes of light and color suggest life and movement within the stillness. This interplay between serenity and vibrancy is central to Wong’s artistic vision, where the natural world becomes both a physical landscape and an emotional space for introspection. The figure’s solitude, set against this fluid, swirling environment, evokes a drifting state of consciousness, as though they are not merely navigating the landscape but floating through their own inner world, caught between lucid reality and abstract emotion.

Wong’s aesthetic combines modernist abstraction with the emotional intensity and intuitive mark-making of Abstract Expressionism, as seen in the crests of impasto across the tactile surface of Untitled, where thick, expressive brushstrokes create a landscape that oscillates between representation and abstraction. His wet-on-wet painting technique—layering pigment before it dries—results in a rich, layered composition that is at once material and ethereal. This process, requiring a fast and light touch, creates a landscape that seems to blur the boundary between reality and dream, much like Henri Rousseau's jungle scenes of a century prior.

“Wong’s paintings—mostly imagined landscapes—are portals to luminous, vibrant, moody places. Though not surreal, they are the product of reverie: poetic concoctions inspired by memory, stray ideas, or the paint itself as he compulsively worked it. Midnight forests glow, somehow, without light, by a painterly magic.”—Raffi Khatchadourian

[Left] Henri Rousseau, The Repast of the Lion, ca. 1907. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Sam A. Lewisohn, 1951, 51.112.5

[Right] Vincent van Gogh, The Sower, Arles, November 1888. The Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Image: The Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Wong often expressed a deep connection to Vincent van Gogh, stating, “I see myself in him. The impossibility of belonging in this world.”iv This affinity was explored in the 2024 exhibition Matthew Wong/Vincent van Gogh: Painting as a Last Resort at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, where an array of Wong’s work—ranging from his early abstractions in ink to the expressive painted landscapes for which he is best known—was paired with a selection of artworks from the museum’s Van Gogh holdings.v Calling the artists “kindred spirits” in their review, The Art Newspaper notes “the shared aesthetics and sensibilities between the two artists,” and cites the show’s curator, Joost van der Hoeven, who describes the “artistic and ‘personal’ relationship” between Wong and “his Dutch Modernist predecessor.”vi Wong’s compositions, though contemporary in sensibility, carry on the Post-Impressionist legacy of using color, texture, and light to evoke deep emotional responses. In Untitled, Wong’s bold, swirling brushstrokes and vivid palette reflect this influence, capturing the psychological depth and emotional resonance Van Gogh achieved in his iconic depictions of the natural world, from golden wheatfields to olive groves and starry night skies.

“Mr. Wong made some of the most irresistible paintings I’ve ever encountered. I fell for the patchworks of color and stippled patterns of his landscapes… It was a visceral experience, like falling for an unforgettable song on first listen… Such relatively unalloyed pleasure is almost as essential as food.”— Roberta Smith

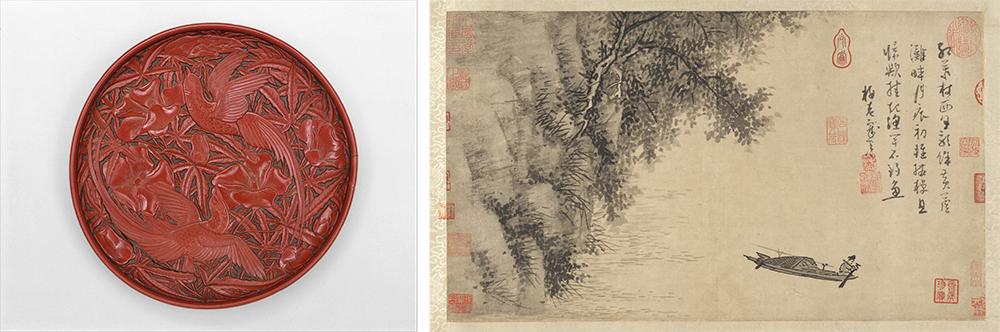

[Left] Attributed to Zhang Cheng Chinese, Dish with long-tailed birds and hibiscuses, mid-14th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, in honor of James C. Y. Watt, 2011, 2011.120.1

[Right] Wu Zhen, Fisherman, ca. 1350. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of John M. Crawford Jr., 1988, 1989.363.33

Though Wong absorbed and gestured toward the influence of Western artists, he did so through the lens of Chinese art, specifically ink painting and decorative lacquerware. The intricacy and precision of Wong’s brush marks in Untitled evokes the detailed surfaces of “Cinnabar,” a Chinese style of carved, vermilion-colored lacquer, where repetitive marks transform flat surfaces into rich, textured compositions.vii Built up layer by layer, the painting’s surface mirrors the craftsmanship seen in this important artistic medium, unique to China, where traditional designs include lush geometric motifs, finely rendered scenes of figures enjoying nature, and lively birds flitting among flowers. This attention to intricacy, combined with the painting’s intimate scale invites close examination, much like lacquerware, revealing layers of detail over time.

Additionally, in this scene, Wong draws from the Southern School of Chinese literati painters, active during the Yuan and Ming dynasties, who emphasized inner realities over realistic depictions.viii These artists often portrayed solitary figures immersed in nature as a metaphor for personal reflection, with boat scenes symbolizing the journey of the soul or mind through a contemplative space.ix One such painter was Wu Zhen, a reclusive figure whose depictions of lone fishermen symbolized the scholar removed from society.x Wong’s Untitled, with its small, isolated figure and flattened perspective, recalls this literati tradition while adding a modern, tactile dimension through his bold textures. The figure in the boat, a psychical traveler adrift in a vibrant landscape, becomes a metaphor for Wong’s probing curiosity and profound interior reflection. This interplay of precision and abstraction, tradition and innovation, resonates with the spirit of Wu Zhen’s poetic colophon:

"Red leaves west of the village reflect evening rays,

Yellow reeds on a sandy bank cast early moon shadows.

Lightly stirring his oar,

Thinking of returning home,

He puts aside his fishing pole, and will catch no more."xi

Collector’s Digest

Since his passing in 2019, Wong has been featured in several major survey exhibitions, including Blue View at the Art Gallery of Ontario (2021–2022), where his work was displayed alongside Picasso's Blue Period paintings; his first U.S. retrospective, The Realm of Appearances, at the Dallas Museum of Art (2022–2023); and most recently, his inaugural European retrospective, Matthew Wong | Vincent van Gogh: Painting as a Last Resort, at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam (March 1–September 1, 2024).

Wong’s work can be found in the public collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Guggenheim Museum, New York; Dallas Museum of Art, Texas; Esteé Lauder Collection, New York; Art Gallery of Ontario, Ontario; and the Aïshti Foundation, Beirut.

i John Yau, “Matthew Wong’s Indelible Impressions,” Hyperallergic, June 19, 2021, online.

ii “The Development of Landscape Painting in China: The Song (960–1279) through the Ming (1368-1644) Dynasties,” Asian Art Museum, Education: Resources, online.

iii Artwork record text, “Wu Zhen, Fisherman, c. 1350,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Collection, Asian Art, online.

iv Ibid.

v John Yau, “Matthew Wong’s Hallucinatory Pilgrimages,” Hyperallergic, April 22, 2018, online.

vi Ibid.

vii Matthew Wong, quoted in Maria Vogel, “Matthew Wong Reflects on the Melancholy of Life, Art of Choice, November 15, 2018, online.

viii Farah Nayeri, “Examining the Connection Between Vincent van Gogh and Artists,” New York Times, Art & Design, February 29, 2024, online.

ix Alexander Morrison, Kindred spirits: Van Gogh and Matthew Wong come together in Amsterdam show, The Art Newspaper, February 21, 2024, online.

x Ibid.

xi Exhibition Overview, “Cinnabar: The Chinese Art of Carved Lacquer,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, online.

Full-Cataloguing

Matthew Wong

CanadianMatthew Wong was a Canadian artist who enjoyed growing acclaim for his lush, dreamlike scenes that play on a rich tradition of art historical precedents. His work depicts the vivid but often melancholy terrain between sleep and wakefulness, lonely landscapes and isolated interiors rendered with a carefree hand and an ebullient palette, yet which contain an ineffable sorrow and a palpable but unnamed longing.

Wong spent his childhood between cultures: he was born in Toronto, Canada and at age 7 moved with his family to Hong Kong where he lived until he was 15, at which time the family returned to Canada. Wong began to experiment artistically already well into his adulthood, first with photography, which he pursued at the postgraduate level at the City University of Hong Kong, and then with painting. A self-taught painter, Wong developed his aptitude for the medium by immersing himself in online conversations with other artists and dedicated personal study of the history of art. His paintings attracted almost immediate attention, but Wong tragically passed away in 2019 just as his work was beginning to receive widespread critical praise.